NZ Biodiversity System Design Q&A Part 2

Part 2 of Toha's responses to the NZ Government's questions on biodiversity market design.

10. What do you consider the most important outcomes a New Zealand biodiversity credit system should aim for?

We see the following outcomes as critical:

To enable the efforts of New Zealanders who already have an intrinsic motivation to protect and restore nature, but lack the financial resources to do so.

This is especially relevant for rural decision makers. As Manaaki Whenua’s survey of rural decision makers has long shown, there are strong motivations among farmers to improve biodiversity and ecosystem health, and a strong preference for native plantings. However, nearly 60% identify the opportunity cost from other land uses as a reason not to plant trees, and nearly 30% identify financial barriers and expense. Therefore, to create a revenue stream from the public value of biodiversity enhancement enables farmers to treat biodiversity as another productive yield, alongside food and fibre.

To create an incentive for New Zealanders who are not motivated for biodiversity improvement, but would do so if it was adequately compensated.

To reset the balance in New Zealand’s climate policy, especially in the agricultural sector, from its current focus on climate mitigation, to a more balanced approach which also addresses climate adaptation and biodiversity improvement.

To recognise, enable and empower the efforts of Māori to exercise their duties of tiakitanga and rangatiratanga.

To create rules and market structures that do not alienate Māori from taonga or whenua, and do not enable benefits to be derived that do not also benefit Māori.

11. What are the main activities or outcomes that a biodiversity credit system for New Zealand should support?

Ultimately, this will be driven by the market itself, with some influence by market design. This is not something that needs to be defined in advance. Nevertheless, Toha sees opportunities for:

Protection, restoration, management and creation of natural ecosystems.

Pest and predator control to enable improved biodiversity outcomes.

Creating incentives for transitional forestry – i.e. credits that reward changes to species composition as exotic trees are thinned or removed and replaced with native tree species.

Enabling tiakitanga activities – i.e. credits that reward activities which are defined by whānau and hapū as beneficial for local ecosystems.

12. Of the following principles [see footnote], which do you consider should be the top four to underpin a New Zealand biodiversity credit system?

Toha generally endorses the principles identified. However, the final selection of principles, as well as their ordering, ought to be achieved through a process with appropriate governance in place. The proposed principles are:

13. Have we missed any other important principles? Please list and provide your reasons.

Do no significant harm: Through a process with appropriate governance, a do-no-significant-harm principle should be considered to precede all other principles. It is critical to recognise that novel market structures carry risks, especially if poorly designed, which may affect the interests of participants as well as non-participants. A robust commitment to monitor and mitigate risks is essential to legitimate the benefits of biodiversity markets, which may or may not eventuate. From a regulator perspective, there is a critical duty to protect the interests of citizens from harms and negative side-effects that may eventuate from new systems. Also, from the perspective of te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Crown has a duty to protect Māori interests from the negative effects of systems such as biodiversity credits that emerge from the kawanatanga sphere.

14. What assurance would you need to participate in a market, either as a landholder looking after biodiversity or as a potential purchaser of a biodiversity credit?

Drawing on Toha’s combined experience in this space, we identify a number of stakeholder concerns that must be addressed in system design to create assurance. We also include mana whenua as a group that needs assurance, because their participation in any such market is inevitable, given ancestral links to land which biodiversity credits will be issued from, even when that land is not in Māori title.

For landholders, we note the following:

Data sovereignty: Measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) for biodiversity credits involves creating significant volumes of data. This raises questions about how this data is used, re-used and stored, especially to protect the rights and interests of those whom the data relates to. Data sovereignty involves ensuring that data is not used for purposes that the creators of the data do not consent to. This has relevance for individual rights and privacy, as well as group rights through frameworks such as Indigenous data sovereignty.

Financial risk: As a type of outcome-based funding, biodiversity credits involve a significant allocation of risk onto the suppliers of credits – i.e. landowners, community groups, or workers in the restoration economy. One prominent risk is that the prospective supplier undertakes a significant amount of work to protect or improve biodiversity, but biodiversity indicators decline for reasons outside of their control (e.g. climate-related shocks, novel pathogens, land management decisions in adjacent areas). Consequently, prospective suppliers will need to be assured that appropriate force majeure provisions are in place, or that outcome metrics are well-selected to avoid such risk, or that activities are the basis of payments when outcomes are too uncertain.

Security and integrity of demand: Suppliers need security of demand to ensure stable cashflow, especially to cover the costs of supplies and labour. Otherwise, nature regeneration and conservation will carry too great an opportunity cost relative to other land uses and activities. Experience from carbon markets, including the NZ ETS, shows that suppliers (in this case, foresters) put a high value on risk relative to returns. In biodiversity markets, given the strong intrinsic values of biodiversity, it is likely that suppliers will accept some level of opportunity cost, as long as cashflow is relatively stable and predictable. Also, given the intrinsic values, many suppliers will likely prefer high-integrity purchasers who are not using biodiversity credits to compensate for biodiversity loss elsewhere (i.e. offsets), or to ‘greenwash’ an otherwise unsustainable business.

For potential purchasers, we note the following:

High methodological integrity: A key enabler for trust in the system is to ensure that the methodologies for measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) are of high scientific integrity. Consequently, the data earns the trust of those who purchase it, because purchasers have confidence that the data is representing real-world impacts. For its own system, Toha has developed a template development process which aligns with academic standards of knowledge application and peer review; and we note that the UK-based Biodiversity Futures Initiative is establishing a similar process of peer review for scientific auditing of methodologies.

Greenwashing risk: Businesses are concerned about purchasing biodiversity credits that expose the purchaser to accusations (justified or not) of false or inaccurate claims. Such concerns are heightened by the known shortcomings of voluntary carbon markets. Methodological integrity can help to reassure purchasers. So too can a greater appreciation of the differences between compensation and contribution claims, which matter significantly to the stringency of each (i.e. any failure in the impact of a compensation claim entails a net-loss of environmental value because the harm is not fully compensated, which is not the case for a contribution claim).

Alignment with international standards: Businesses are under growing expectations to provide data to meet various mandatory and voluntary reporting requirements, including climate and nature-related risks (e.g. TCFD and TNFD) and sustainability standards for international trade (EU’s ESRS). Due to the high potential transaction costs, it is important that reporting requirements are as harmonised and interoperable as possible. This creates an opportunity for, if not an expectation that, biodiversity credits are aligned with international standards, so that biodiversity credits can be used by holders to demonstrate alignment with relevant nature-related standards.

For mana whenua, we note the following:

Māori rights and interests: There are significant unresolved issues from the WAI 262 Claim on indigenous flora and fauna, and cultural and intellectual property. The report by the Waitangi Tribunal claim makes recommendations on how to protect mātauranga Māori, taonga, and natural resource management. However, the findings and recommendations are still under consideration by the Crown. This indeterminacy raises challenges for the implementation of biodiversity credits which, depending on how they are implemented, might declare novel property rights on habitats or species.

Indigenous data sovereignty: This ensures that Indigenous peoples have a say in what happens to data collected for and about them. In Aotearoa New Zealand, Te Mana Raraunga, the Māori Data Sovereignty Network, define Māori data as ‘data produced by Māori or that is about Māori and the environments [they] have relationships with’ (Te Mana Raraunga Charter, 2016). Consequently, insofar as biodiversity credits do create data that relate to whenua and taonga species, Māori must be involved in the governance of data.

15. What do you see as the benefits and risks for a biodiversity credit market not being regulated at all?

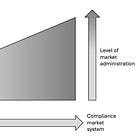

This is not a tractable question because all markets are subject to rules and regulation, to a lesser or greater extent (see Section 4 of this submission, especially Figure 1). This might be indirect, such as when market activities fall under the purview of legislation like the Fair Trading Act 1986 or the Resource Management Act 1991. However, direct rules are needed to ensure fair and just outcomes, and to mitigate cheating and exploitation. Thus, the proper question relates to the relative risks and benefits of under-regulation or over-regulation, and to what extent government regulation should be balanced against self-regulation.

The risks of under-regulation are as follows:

Māori interests: Without rules in place, there are significant risks to Māori from an unregulated market, particularly in relation to the commercialisation of taonga and whenua. Through biodiversity markets, there are opportunities to benefit from digital sequence information on genetic resources, or spatially-located nature-positive claims. As per international guidance, it is critical that this occurs with the free, prior and informed constent of Indigenous peoples and local communities, and that Indigenous peoples benefit from any proceeds that eventuate. Te Tiriti o Waitangi granted the Crown the right to establish the kawanatanga to protect Māori interests from exploitative behaviours, and it follows that that responsibility remains today, including to protect Māori interests from new schemes like biodiversity credits which create novel property rights that might have implications for taonga.

Additionality: Additionality is a fundamental principle in carbon and biodiversity markets; however its demands differ in relation to contribution claims vis-a-vis compensation claims. When a credit purchaser is making a compensation claim (i.e. offsetting), the claimant must ensure that the credit is genuinely additional to business-as-usual in order to credibly claim that it ‘neutralises’ an emission or unit of biodiversity loss. If it is not genuinely additional, the offset will permit a net gain in emissions or a net loss to environmental value. By contrast, contribution claims do not purport to neutralise an actual harm, rather to make contributions to climate mitigation or biodiversity enhancement that go beyond business-as-usual. Consequently, the principle of additionality is not as demanding (see also our answer to Question 8). However, additionality is still important, especially for purchasers or investors, to ensure that the payment provided for the credit has resulted in the outcomes or activities associated with it. Some of the risks associated with additionality, which ought to be the concern of regulators, are:

Misleading claims about the use of proceeds from a credit sale, where the proceeds are not primarily being used to fund the outcome or activities that were advertised. Government already must ensure that environmental claims by businesses and individuals are substantiated, truthful, and not misleading, as per the Fair Trading Act 1986.

Double-counting is a related issue which ought to be a concern for regulators. That is, a landowner might knowingly or unknowingly sell the same biodiversity improvement to two different accreditation schemes, which undermines the additionality of one of those claims. The creation of a single register would enable this risk to be managed.

Undermining the additionality of high-integrity carbon and biodiversity credits by the issuance of low-integrity biodiversity credits to fund conservation activities, and therefore impeding the future revenue opportunities that a high-integrity issuance might attract for land owners. This is especially risky for conservation, because conservation groups often work on other people’s land, so any biodiversity credits that result from outcomes or activities could interfere with the additionality of subsequent claims. Given the complexities of environmental credit markets, this could easily occur without the landowner’s consent, because the landowner or even the issuer does not fully understand the implications for future revenue opportunities.

The risks of over-regulation are as follows:

Inadequate governance: The experience of the NZ ETS should give pause to a highly managed scheme where the Government is heavily involved in market administration. It is not clear that the Government has sufficient capabilities and proper institutional arrangements to govern the NZ ETS effectively. This scheme has proven to be unexpectedly vulnerable to speculative behaviour, which has undermined its capacity to deliver on its environmental objectives. The stringency of the NZ ETS is vulnerable to politicised decisions that favour vested interests and electoral considerations. The NZ ETS also lacks adaptive management capability to respond swiftly to shortcomings and surprises, not least because the process of adjusting settings is very slow. Biodiversity markets are potentially another order of complexity again, particularly in regard to MRV processes. Unless the Government has a clear and frank diagnosis of NZ ETS governance issues, then there are significant execution risks for taking a strong role in market administration on another market mechanism of equal or greater complexity.

Crowding out rangatiratanga and community interests: Over-regulation from Government invariably means that governance will not be devolved to other sources of authority, especially Māori who must play a role in the governance of any internationally credible system. Because biodiversity is inherently locally specific, however, it is vital that whānau and hapū, as well as local ecologists and conservation groups, can participate in the co-development of the scheme (e.g. through the creation of MRV methodologies) to share their locally specific knowledge.

Undermining voluntarism: As discussed in Section 4 on the roles of government, if the proposed scheme is voluntary market, it is critical that the Government not play a strong administrative role, or else it may undermine the preconditions for voluntary participation. This includes the stakeholder buy-in and legitimacy that comes from co-design and co-development, and the capacity of market development processes to facilitate market fit.

16. A biodiversity credit system has six necessary components (see figure 5). These are: project provision, quantification of activities or outcomes, monitoring measurement and reporting, verification of claims, operation of the market and registry, investing in credits.

To have the most impact in attracting people to the market, which component(s) should the Government be involved in? Please give your reasons.

We address these issues in Section 4 of this submission on the roles of government. If this is a voluntary market, then the majority of the market components should be led by market participants, with Government involvement largely relegated to its regulatory role. The more the Government is involved in market administration, the more it bears the burdens of compelling participation, which shifts this from a voluntary to a compliance market.

Government regulation should largely be upstream. So, rather than engage in market building activities directly, it should monitor and regulate those entities that engage in project provision, quantification of activities or outcomes, monitoring measurement and reporting, verification of claims, and operation of the market and registry. In particular, the Government has an important role in ensuring that the claims underpinning the issuance of credits are credible and of sufficient integrity. Specifically, this relates to its obligations under the Fair Trading Act 1986, where the Government must ensure that environmental claims by businesses and individuals are substantiated, truthful, and not misleading.

Investing in credits: The Government has an important role in market enablement, and the purchase of credits could be critical for accelerating market development, and stimulating and stabilising innovation, especially in the early phases of market development. Economists have long recognised that direct support from Government is critical to support research and development, and to enable new technologies to mature along the value chain. This is especially important for technologies that support Government to achieve its policy objectives, and that create knowledge spillovers which benefit other policy objectives, and therefore create a public benefit. Over the longer run, Government could use procurement to achieve policy objectives, especially to address shortfalls where natural market demand is lagging.

17. In which areas of a biodiversity credit system would government involvement be most likely to stifle a market?

Developing monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) methodologies: This should be achieved by sector experts using tested approaches to quality assurance and control, such as peer review. Government has an important role in enabling this process, especially through support for public research, but it is critical for legitimacy that the development is achieved by research experts. Toha is already achieving this through the use of researchers and local experts for development of its claims templates, along with scientific auditing for quality control.

Administration of data: It is not clear that the Government has the capacity to administer the data that a biodiversity credit system would produce, nor that the Government could achieve this in a manner consistent with ideals of Indigenous data sovereignty and self-sovereignty. We recommend that an open public data infrastructure is developed collectively, with decentralised governance that enables ownership and governance rights from all data creators. We discuss governance further in Section 3 of this submission.

Project provision: As discussed in Question 4, there is a risk that biodiversity credits on public land could crowd out market demand that might otherwise go to individual landowners and whenua Māori collectives who urgently need new forms of funding and financing.

18. Should the Government play a role in focusing market investment towards particular activities and outcomes and if so why? For example, highlighting geographic areas, ecosystems, species most at threat and in need of protection, significant natural areas, certain categories of land.

A market scheme like biodiversity credits is likely to be strongly influenced by the preferences of credit buyers, which may reflect subjective biases rather than scientifically-informed objectives. For example, it is conceivable that the buyers of biodiversity credits will favour charismatic species, such as birds and lizards, rather than less charismatic species like invertebrates or molluscs which may nevertheless need urgent assistance. This risks creating outcomes that lack ecological integrity and that neglect important ecological functions that ‘uncharismatic’ species also provide.

However, as long as the biodiversity credit scheme is voluntary, then the Government should not play a heavy-handed role in determining where market investment goes, because this may interfere with the intrinsic motivations of credit purchasers. Rather, Government should monitor biodiversity outcomes, identify target areas, then use its own policy levers (e.g. regulation, subsidies, information) to improve biodiversity outcomes in those areas where private finance is falling short. It is for this reason that the biodiversity credit system should not be treated as an alternative or a substitute for public finance and public policy, but rather as a complement.

There are less direct ways that Government can enhance alignment with the Government’s policy objectives and processes. For instance, if the market is neglecting certain species or habitat types, the Government could direct research and innovation funding toward the creation of MRV methodologies, establishing baselines for evaluating impact, and/or quantifying the benefits of environmental protection.

If the Government does wish to direct private finance, however, then it should intently shift from a voluntary scheme to a more compliance-based scheme which compels participation and allocates proceeds to target areas. For instance, the Government could set quotas that must be met through the purchase of credits or tradeable certificates that represent verifiable biodiversity improvement. Alternatively, the Government might require participants to invest into a funding pool which is allocated according to conservation need, with a priority on habitats and/or species that are underfunded or acutely at risk. It is critical, however, that any such shift is recognised as a move toward a compliance market and away from a voluntary market, which is the focus of this consultation. See Section 4 for further discussion of these trade-offs and market shaping roles.

19. On a scale of 1, not relevant, to 5, being critical, should a New Zealand biodiversity credit system seek to align with international systems and frameworks? Please give your reasons.

(4) because local flexibility is needed to be sensitive to unique biophysical and cultural elements. However, for credibility and to ensure investor interest, there needs to be alignment with international reporting standards especially, so that companies can use biodiversity credits to satisfy international market expectations (e.g. EU’s ESRS), or climate and nature-related risk disclosures (i.e. TCFD and TNFD). Currently, there is a diversity of methodologies internationally and no strong consensus around particular standards, so an adaptive approach is prudent in case any such consensus does emerge.

20. Should the Government work with private sector providers to pilot biodiversity credit system(s) in different regions, to test the concept?

If you support this work, which regions and providers do you suggest?

Yes, the Government should support regional pilots. Specifically, the Government should urgently implement recommendation (R.35) in the Ministerial Inquiry into Land Use (the Inquiry) for a world-leading regional pilot for biodiversity credits in Tairāwhiti and Wairoa.

Learning from the lessons of the ETS, there is significant value in taking an incremental, adaptive approach to biodiversity markets, because the effects of biodiversity credits cannot be properly predicted or anticipated. A regional pilot in Tairāwhiti and Wairoa will produce insights and lessons that will benefit other regions, while also providing material improvements to landscape resilience. As the Inquiry noted: ‘Right now, the Tairawhiti environment is on the verge of collapse, yet can become a living laboratory, providing evidence and lessons for adapting to a climate-changing world.’

21. What is your preference for how a biodiversity credit system should work alongside the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme or voluntary carbon markets?

(a) Little/no interaction: biodiversity credit system focuses purely on biodiversity, and carbon storage benefits are a bonus.

(b) Some interaction: biodiversity credits should be recognised alongside carbon benefits on the same land, via both systems, where appropriate.

(c) High interaction: rigid biodiversity ‘standards’ are set for nature-generated carbon credits and built into carbon markets, so that investors can have confidence in ‘biodiversity positive’ carbon credits.

Please answer (a) or (b) or (c) and give your reasons.

This question is addressed to a significant extent by Toha’s submission to the ETS Review and Permanent Forest Category (see Appendix 1). Here we reiterate this position in the light of this consultation.

Generally speaking, the optimal policy design will involve at least one policy instrument for each policy target – that is, ≥1 instrument for carbon and ≥1 instrument for biodiversity. These instruments can and often should overlap, but also should retain their distinctiveness. Empirical analysis reinforces the theoretical expectation that pursuing two or more policy objectives with one instrument is likely to result in suboptimal outcomes.

This speaks to the importance of the current consultation. In New Zealand, we have an established compliance carbon market, the NZ ETS, which is designed to serve the policy objective of least-cost emissions reductions. However, there is no comparable economic instrument for biodiversity (or indeed for other key objectives like climate adaptation). These deficits in the instrument mix are best addressed by the addition of new policy instrument, because reforming the NZ ETS to serve two objectives (i.e. carbon and biodiversity) is likely to produce suboptimal outcomes for both.

Consequently, an ideal instrument mix for the intertwined objectives of climate mitigation and biodiversity will involve at least two instruments that are designed to be interoperable; for instance, a biodiversity payment can be stacked on a carbon payment. The NZ ETS currently provides a payment for carbon (although, if the Government chooses to decouple forestry from the NZ ETS, this may need to be replaced with another economic instrument to pay for carbon removals). A voluntary biodiversity credit system is one instrument which could derive a payment for biodiversity. If the biodiversity credit system is designed to overlap with the NZ ETS, then it will help to reduce the opportunity cost between fast-growing exotics and slower-growing natives, because only the native forest could access the biodiversity payment in addition to the carbon payment, thus improving its economics.

This issue of biodiversity-carbon stacking raises questions about additionality – i.e. does the biodiversity payment undermine the claim of additionality for carbon? As a member of the Biodiversity Credits Alliance, we are aware that this issue is being debated internationally and remains unresolved. For New Zealand, we recommend the creation of a regulatory sandbox where regulators and biodiversity credit issuers can work through such issues together.

22. Should a biodiversity credit system complement the resource management system? (Yes/No)

For example, it could prioritise:

• Significant Natural Areas and their connectivity identified through resource management processes

• endangered and at-risk taonga species identified through resource management processes.

Similarly to Question 4, this prioritisation is ultimately a matter for the market, because a voluntary market depends upon credit purchasers being able to invest in what they value. What is more important is ensuring that relevant indicators, such as its linkage to an SNA, is included in the metadata for each credit, so that the market can differentiate accordingly. The real question for Government is how to use its market shaping powers to prevent misalignment with the resource management system, and ideally to maximise positive synergies. This might involve R&D funding to support the development of credit methodologies that align with SNAs, or public purchases of credits from SNAs to support their public value.

23. Should a biodiversity credit system support land-use reform? (Yes/No)

(For example, supporting the return of erosion-prone land to permanent native forest, or nature-based solutions for resilient land use.)

Yes: land-use reform is a legitimate and feasible goal for a biodiversity credit system. In particular, the retiring of vulnerable pastoral land from agricultural production (i.e. erosion-prone land, riparian margins) in a revenue-neutral way is one of New Zealand’s greatest opportunities for environmental remediation and improvement – and one which would deliver significant integrated benefits for biodiversity, climate adaptation, long-lived carbon storage, and historical reparations. However, directing a biodiversity credit system toward a strategic goal will require a market-shaping or market-steering approach from the Government to ensure that the system incentivises land use decisions that align with land use strategy.

Land use change will be a natural outcome of any successful biodiversity credit system that operates at scale. However, trends in land use change will reflect whatever incentives are actually created by its payment system. These may not necessarily align with evidence-based policy objectives. A market scheme like biodiversity credits is likely to be strongly influenced by the subjective preferences of credit buyers, which may reflect personal biases rather than scientifically-informed policy objectives. For example, it is conceivable that the buyers of biodiversity credits will favour habitats that support charismatic species like forest-dwelling birds, rather than habitats like native grasslands. This could result in underfunding of the latter, or even the ecologically inappropriate establishment of native forest on grasslands or peatlands that were not historically forested.

To avoid these perverse outcomes, Government is likely to need to play a proactive role, for instance, by:

using the public procurement lever to redress underfunding for certain habitats or species through the purchase of corresponding biodiversity credits;

creating regulation to restrict perverse outcomes, such as the creation of ecologically inappropriate ecosystems; for instance, the issuance of biodiversity credits for native forest could be prohibited from areas that were historically a non-forest land type;

a requirement that buyers purchase biodiversity credits on the basis of conservation need, rather than subjective preference; for instance, participants could invest into a funding pool which is allocated according to conservation need, with a priority on habitats and/or species that are underfunded or acutely at risk.

With these caveats in mind, it is worth highlighting the benefits of using a market mechanism, such as biodiversity credits, to achieve objectives in land-use reform. Markets exert change through the influence of economic enablers and incentives, rather than by compulsion or mandate. In land use, this can help to preserve human agency and decision-making power, because it does not dictate how landowners should manage their land, only reshapes their choice set by creating new economic enablers and incentives. Therefore, a well-designed market mechanism not only creates space for human agency, it also creates space for people to make place-based decisions that employ localised knowledge. This includes site-specific knowledge, such as which slopes are erosion-prone, or availability of sunlight in a certain area. It also includes mātauranga Māori such as maramataka or knowledge about eco-sourcing. Nuanced decisions at this level cannot easily be made by mandates from centralised authorities, thus market instruments can be an effective distributional mechanism for enabling place-based choices.

That said, a poorly designed market can be coercive when it favours the economics of one option to such an extent that people cannot reasonably choose otherwise, even when this choice cuts against the decision maker’s values. Arguably, this has occurred through the NZ ETS which, in the absence of other instruments, has created a strong incentive for exotic afforestation, even when rural decision makers show a widely-held preference for native tree species. These trade-offs between individual choice and public benefit will need to be carefully considered for a biodiversity credit system too, in order to retain the consent and legitimacy of the public.

Back to: