NZ Biodiversity System Design Q&A Part 1

Part 1 of Toha's responses to the NZ Government's questions on biodiversity market design.

1. Do you support the need for a biodiversity credit system (BCS) for New Zealand? Please give your reasons.

Toha supports the need for a biodiversity payment system – whether by biodiversity credits or some other mechanism – for the following reasons:

To create a fair payment for the work involved in nature repair and regeneration.

To enable on-farm biodiversity to be recognised by markets as an important agricultural yield, alongside food and fibre.

To create an alternative payment system for nature-based carbon removals which enables the gradual phase-down of carbon offsetting, so that an increased proportion of future removals can count purely as negative emissions in the national accounts.

To substitute for the loss of revenue through the ETS in the event that the New Zealand Government chooses to decouple forestry removals from the ETS (as a consequence of the 2023 ETS Review).

To compensate Māori forest owners for any transition of forestry removals out of the ETS, in recognition of the unjust treatment of Māori interests through the implementation of the ETS.

To create the right incentives for afforestation within the Permanent Forest Category by enabling stacked payments for carbon removals and biodiversity uplift, thereby improving the financial returns for native forests and therefore the opportunity cost for faster growing exotics.

To create the right incentives for transitional forestry by enabling payments for changing the species composition in a forest – i.e. from exotic-dominated to native-dominated forest.

To create revenue opportunities for types of ecosystem restoration that are currently ineligible for inclusion in the ETS (e.g. small forests, riparian plantings, wetland restoration, soil restoration, coastal habitat, freshwater ecosystems, marine ecosystems).

To create revenue opportunities for the protection and restoration of ecosystems such as pre-1990 native forest and wetlands, which are not eligible in the ETS and lack other economic supporting mechanisms.

Toha is agnostic on whether a biodiversity credit system will achieve these goals, because success will depend on the design of any such system. A poorly designed system could cut against some or all of the goals implied above, and also create other problems. Consequently, in addition to an analysis of opportunities (as per above), the Government needs to undertake a far more rigorous and comprehensive risk analysis than the bullet-points provided on p.30 of the discussion document. Some risks that need to be better articulated are:

The biodiversity credit system becomes a means of inadequate compensation of environmental harms, either directly by being co-opted for biodiversity offsetting that results in net biodiversity loss, or indirectly by enabling companies to make nature-positive claims without addressing biodiversity loss in their own value chains.

The dilution of existing property rights by the creation of tradeable claims of biodiversity uplift and/or avoided biodiversity loss, which may carry liabilities if the improvement is reversed.

The commercialisation of taonga species or habitat for economic gain, without the consent of whānau and hapū, or a fair distribution of benefits.

The risks of mismanagement or misuse of data that is created by MRV for biodiversity credits, which violates self-sovereign or Indigenous rights over data, exposes landowners to loss of privacy or consent, or results in an unjust distribution of the benefits of data commercialisation.

The prospect of misallocating Government effort toward a policy option which could have been better directed toward other options, such as increasing budget allocations, green fiscal policy reform or stronger environmental regulation. This is especially relevant if there is limited voluntary demand for a biodiversity credit market.

The imposition of regional or global standards which do not work well in the local context of Aotearoa New Zealand, or result in perverse outcomes.

The creation of unbalanced or biased environmental outcomes, due to market preferences or market structure - e.g. a bias toward funding the creation of new habitat rather than protecting existing habitat, or a charismatic species bias that favours some species over others.

2. Below are two options for using biodiversity credits. Which do you agree with?

(a) Credits should only be used to recognise positive actions to support biodiversity.

(b) Credits should be used to recognise positive action to support biodiversity, and actions that avoid decreases in biodiversity.

Please answer (a) or (b) and give your reasons.

For a voluntary market, design issues such as Question 2 should ultimately be resolved by the processes of market development which are responsive to supply- and demand-side needs, rather than ex ante decisions by the Government.

Specifically, if potential purchasers of biodiversity credits are willing to pay for credits that represent avoided biodiversity loss (2b) as well as biodiversity uplift (2a), then there is no reason to prohibit this, least of all by an ex ante design choice by the Government. What matters is whether a sufficiently robust MRV methodology can be developed to assure that avoided biodiversity loss was enabled by the proceeds of the credit.

We note that credits for avoided biodiversity loss, or protection, are a part of emerging biodiversity credit systems globally., The inclusion of such credits also present an opportunity to fund the protection of pre-1990 indigenous forest, and other ecosystem types, which are not eligible for the NZ ETS and therefore lack an income stream. When the ETS was being designed, the exclusion of pre-1990 indigenous forest was perceived as unfair by many hapū and whānau who had chosen to protect such habitat, and therefore avoiding emissions and biodiversity loss. By supporting active protection through the issuance of biodiversity credits, the lack of revenue for existing habitat could be addressed without the issuance of additional emissions allowances (which is what inclusion in the ETS would involve).

Verifying avoided loss can be challenging. Lessons need to be learned from voluntary carbon markets, especially the issuance of carbon credits for avoided deforestation which has recently been subject to high-profile criticism. However, as long as biodiversity credits are intended as contribution claims rather than compensation claims, the stakes are lower (because the credit is not being used to compensate, or neutralise, the impact of a harm elsewhere). These differences must be carefully considered before generalising the flaws of carbon markets.

Additionally, the opportunities for avoided biodiversity loss differ in New Zealand. Internationally, the issuance of carbon credits for avoided loss tend to relate to land use change – i.e. whether forest clearance was certain to occur (or not). This has proven difficult to establish, because it is based on hypotheticals about what communities were planning to do (or not). However, a major source of biodiversity loss in Aotearoa New Zealand comes from invasive pests and predators. Accordingly, biodiversity credits could be issued to fund pest and predator control by modelling the likely biodiversity losses under a business-as-usual scenario, then issuing biodiversity credits to fund ecosystem management that forestalls these expected declines. This involves predictions about the stable behaviour patterns of pest and predator species, which can be achieved with greater certainty than predictions about the ever-changing intentions of humans. Thus, the proceeds of biodiversity credit sales can be transferred to verifiable activities which arrest and reverse biodiversity decline.

With these issues in mind, even though the Government should avoid imposing ex ante design choices upon a voluntary market, this does not mean that the Government should be indifferent to how it evolves. If credits for avoided biodiversity loss do emerge, the Government should ensure that the MRV methodologies and additionality claims are robust. Also, the Government should contemplate what role it plays (if at all) if the voluntary market does not develop credits for avoided loss, only for biodiversity uplift. If it is likely that private finance is better suited to restoration rather than conservation, then the Government should make clear that it will address avoided biodiversity loss through alternative policy tools, or the use of public finance to support credits for avoided loss, or imposing purchase obligations on private parties.

3. Which scope do you prefer for a biodiversity credit system?

(a) Focus on terrestrial (land) environments.

(b) Extend from (a) to freshwater and estuaries (eg, wetland, estuarine restoration).

(c) Extend from (a) and (b) to coastal marine environments (eg, seagrass restoration).

Please answer (a) or (b) or (c) and give your reasons.

Again, the Government should not make ex ante design choices about the scope of voluntary market. Consequently, Toha favours the openness of Option (c), because it is not the ecosystem type which ought to determine eligibility, it is the integrity of impact verification.

In principle, it should not matter if the biodiversity credit is being issued for terrestrial, freshwater or marine-based improvements. As long as the measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) protocol is robust and competently administered and audited, then the ecosystem type should not matter.

In reality, it is likely that the development and implementation of MRV protocol for marine-based ecosystems will be more constrained, because of the highly dynamic nature and inherent complexities of marine environments. Nevertheless, even though many terrestrial indicators will likely be easier to operationalise, it is also likely that the most challenging terrestrial indicators will more difficult to verify than the least challenging marine indicators. In such instances, there is no reason why the development and implementation of marine MRV should not proceed.

In particular, these boundaries of inclusion should not be pre-determined by regulators. Rather the validity of MRV protocol should be determined by rigorous scientific processes, such as peer review by relevant experts and the evaluation of pilots. This should be undertaken by assessors with relevant expertise to decide, not by regulators who may lack such expertise in-house. However, regulators may play a role in determining whether such a quality control and quality assurance process was undertaken competently.

4. Which scope do you prefer for land-based biodiversity credits?

(a) Cover all land types, including both public and private land including whenua Māori.

(b) Be limited to certain categories of land, for example, private land (including whenua Māori).

Please answer (a) or (b) and give your reasons.

Again, this is not a question to be addressed ex ante, rather by supply and demand. What is more important is ensuring that accurate classifications of land type are included in the metadata for each credit, so that the market can differentiate between credits from different land types and price these credits accordingly.

However, one critical question is whether public land should be included. Given the size of the national conservation estate, the potential supply of credits is substantial. If these credits were permitted to exhaust market demand, this deprives private land owners and whenua Māori collectives of new sources of funding.

Consequently, we recommend that the Government does not act as a supplier of biodiversity credits, especially in the early stages of the scheme. This is comparable to how the NZ ETS already operates where Crown land is excluded from eligibility – although exceptions could and should be made for mana whenua or community groups who are operating on Crown land to improve biodiversity outcomes. Rather, Government should limit its market participation to the demand side as a potential purchaser of biodiversity credits to support market development, to use biodiversity credits to achieve biodiversity policy objectives, and to bridge funding shortfalls where market demand is lacking.

5. Which approach do you prefer for a biodiversity credit system?

(a) Based primarily on outcome.

(b) Based primarily on activities.

(c) Based primarily on projects.

Please answer approach (a) or (b) or (c) and give your reasons.

Option (a) and (b) only, for the following reasons:

Option (c) has the risk of diluting the intended purpose of a biodiversity credit as a standardised unit of exchange that reflects the value of genuine biodiversity improvements. This is evident in the response to Australia’s Nature Repair Market, which proposed units on a per-project basis with no clear connection to actual biodiversity gains. A submission by a consortium that included NatureFinance and Pollination argued that: ‘Projects should instead generate credits as a result of measured and verified per-unit enhancement and/or protection of biodiversity… using a holistic, robust, standardised, and continuously updated metric’. The submission notes that a per-project approach means that each biodiversity certificate (or credit) will be priced very differently, given the enormous variability in size and value of the underlying project. This would also bias the market toward large purchasers (corporate or government) of large-scale projects which could signify marginal biodiversity improvements over large areas, rather than more impactful improvements in smaller ecological niches.

Toha supports Option (a) with its emphasis on outcomes. The ideal biodiversity credit system will have a clear connection to real-world improvements to native biodiversity for the following reasons:

Technological developments in bioacoustic monitoring, remote imagery, eDNA metabarcoding and machine learning are creating new opportunities to drive down the cost, effort and capability required to undertake scientifically robust monitoring, reporting and verification.

A focus on outcomes is increasingly important for private and philanthropic funders of conservation and nature repair, who need to be able to demonstrate value for money to shareholders, customers, and other stakeholders.

Policy-relevant targets such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework are ultimately connected to outcomes, not effort.

Monitoring of outcomes improves our collective knowledge of environmental trends by generating new biodiversity data. If this data is open and accessible, it could have spillover benefits for environmental management beyond credit markets, including improving adaptive management to respond to climate-related stressors.

Toha also supports Option (b) by recognising that verification of activities will play an important role, especially in the early phases of system development. This is for the following reasons:

Labour is itself valuable and deserves to be fairly remunerated, irrespective of outcomes. The professionalisation of nature-based jobs would help to lift the sector’s impact and efficiency, which biodiversity credits could enable as a form of outcomes-based funding.

Outcomes will sometimes be too technically difficult to measure and verify with sufficient certainty, so it will sometimes be justifiable to issue credits on the basis of activities that strongly correlate with the desired outcomes as a proxy.

Measurement and monitoring of outcomes will sometimes be too expensive, which increases the transaction costs of the biodiversity credit and therefore reduces the quantum of the payment. Consequently, the verification of activities can serve as a more cost-effective proxy.

Biodiversity is inherently complex, which makes it hard to attribute cause and effect, and therefore to attribute outcomes to activities. Confounding variables can influence outcomes irrespective of activities, such as the occurrence of a mast year, a climate-related extreme weather event, the presence of a novel disease or pathogen, or land management decisions in a neighbouring property. Again, accreditation of activities might be justifiable to mitigate such risks.

6. Should there also be a requirement for the project or activity to apply for a specified period to generate credits?

Please answer Yes/No and give your reasons.

Ultimately, this is a question for voluntary market developers to navigate by devising a workable solution that meets supply and demand-side needs.

International precedents are likely to inform this process. A recent Pollination review notes that nature-based solutions carbon credit projects typically end after 25–30 years, although carbon stocks can be further protected by the extension of legal protections over the land after the crediting period has ended. These ‘permanence periods’ are typically between 25 and 100 years. But it is also recognised that an indefinite crediting period might be required, because legal protections are challenging to administer.

7. Should biodiversity credits be awarded for increasing legal protection of areas of indigenous biodiversity (eg, QEII National Trust Act 1977 covenants, Conservation Act 1987 covenants or Ngā Whenua Rāhui kawenata?

Please answer Yes/No and give your reasons.

No, as per Question 5, Toha takes the view that biodiversity credits should be awarded on the basis of outcomes and activities, not merely the certification of a project which falls under a covenant. However, the application of a covenant is itself a type of activity which correlates with positive biodiversity outcomes, because it manages the risk of future land-use change. Consequently, the establishment of selected covenants (e.g. QEII National Trust Act 1977 covenants, Conservation Act 1987 covenants, or Ngā Whenua Rāhui kawenata) should be treated as an activity that could contribute to the issuance of the biodiversity credit.

Potentially, where a site is eligible for a covenant, its establishment might be a mandatory requirement for the issuance of the biodiversity credit, as a mechanism for increasing the likelihood that biodiversity improvements will persist.

8. Should biodiversity credits be able to be used to offset development impacts as part of resource management processes, provided they meet the requirements of both the BCS

system and regulatory requirements?

No, a clear separation should be made between a voluntary biodiversity credit market and a mandatory biodiversity offsetting scheme. As discussed in Section 4, voluntary and mandatory markets have very different administrative needs, which need to be taken into consideration. Moreover, the association with offsetting is a major source of reputational risk for the biodiversity credit system. The wrong approach could seriously undermine the perceived value of biodiversity credits among key stakeholders and the wider public.

Internationally, a strong distinction is being drawn between biodiversity credits and biodiversity offsets. To use the emerging language of Paris-era carbon markets, biodiversity offsets are a compensation claim whereas biodiversity credits are a contribution claim. As the Biodiversity Consultancy explains: ‘While biodiversity offsets and biodiversity credits share some design features, credits are distinct from offsets in terms of their role and function in delivering nature-positive outcomes… Biodiversity offsets are designed to compensate for residual negative biodiversity impacts as the last resort in a mitigation hierarchy of actions to address known site-based impacts, which should first prioritise prevention… [By contrast], biodiversity credits could be used for positive contributions to nature, for example going beyond the mitigation hierarchy to make a proportional contribution towards addressing historical impacts on biodiversity… Voluntary biodiversity credits are most likely to deliver verifiable positive biodiversity outcomes if they are not used as biodiversity offsets.’

Therefore, it would be inconsistent with emerging international guidance to use ‘biodiversity credits’ for offsetting purposes (i.e. as compensation claims), even where there are commonalities in MRV standards. To avoid confusion, maintaining the distinction between contribution and compensation claims will be important, as a matter of product differentiation. This will also help biodiversity credits (i.e. contribution claims) to maintain distance from biodiversity offsetting schemes, which are contentious historically and likely to remain contentious because of their inherent incoherences and inconsistencies.,

(It is worth noting parenthetically that the definition of biodiversity credits as contribution claims, and contribution claims only, may be difficult to sustain. This is because of the public’s familiarity with ‘carbon credits’ which are commonly used for offsetting purposes (i.e. compensation claims). This association may prove difficult to overcome, which would mean that biodiversity credits would be exposed to the loss of legitimacy of offsetting schemes. Notably, some other schemes are already using alternatives to the language of credits: Plan Vivo’s Biodiversity Standard and Australia’s Nature Repair Market Bill 2023 refer to ‘biodiversity certificates’. In a country where the public is familiar with carbon credits as offsets through the NZ ETS, the New Zealand Government should think carefully about the reputational risks of the language of ‘credits’ and whether an alternative like ‘certificates’ or ‘units’ might help to enforce the distinction with offsetting.)

Another reason for maintaining a clear distinction with biodiversity offsetting is that offsets must achieve specific standards of additionality, or else the compensation might result in a net-negative outcome for nature. To elaborate, a biodiversity offset needs to be strictly additional – that is, the proceeds of the offset sale need to result in outcomes that go beyond business-as-usual. If they do not, then the offset will fail to neutralise the loss being compensated, because it creates a permit to cause biodiversity loss on the basis of outcomes that would have occurred anyway. Furthermore, if the compensation claim is based on outcomes that are inferior in quality or quantity than those being claimed, it undermines the ‘like for like’ logic that underpins the compensation claim. By contrast, the stakes are lower for a biodiversity credit (i.e. a contribution claim), because it does not purport to compensate for an existing loss. Even if the actual outcomes are less than claimed, a biodiversity credit may still result in a net biodiversity gain, because it still constitutes an impact that goes beyond business-as-usual, even if that impact is less than what was claimed. Accordingly, a biodiversity credit market to serve contribution claims can be held to a lower regulatory standard, which reduces its overall transaction costs. If, however, the market were open to offsetting transactions for compensation claims, then all units may need to reach the minimum standard for offsets, which increases the transactions costs for contribution claims as well as compensation claims. Moreover, this necessitates greater involvement from the Government as a market administrator because of the mandatory nature of the offsetting requirements and the Government’s duty to ensure that policy objectives (i.e. no net-loss) are met.

To sum up, we recommend a clear separation between the biodiversity credit scheme and biodiversity offsetting, such as regulatory requirements in the National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity (NPS IB). In order to achieve the NPS IB’s objective of net biodiversity gain, the administration of offsetting requires a high standard of integrity and stringency, which would impose excessive transaction costs on contribution claims if issued through the same system. Moreover, a separation of systems is sensible to avoid confusion between contribution claims and compensation claims, and especially to protect the former from controversies that relate only to the latter.

9. Do you think a biodiversity credit system will attract investment to support indigenous biodiversity in New Zealand?

Please give your reasons.

Internationally, there is significant interest in biodiversity credits. However, there is significant uncertainty about the nature of market demand. Who are the buyers of such credits? What are their motivations?

We see a roadmap to investment as follows:

In the near term, the stacking of a carbon credit and a biodiversity credit can enable a high-quality, high-integrity compensation claim for hard-to-abate emissions in voluntary markets. There is already existing demand for nature-based carbon, and evidence of a market premium.

In the mid-term (mid- to late-2020s), we see a growing market for biodiversity credits that are associated with risk reduction through ecosystem-based adaptation, or nature-based solutions for climate adaptation. This might include native forests on erosion-prone steep slopes, lowland wetlands for flood mitigation, restoration of river catchments, coastal habitat to address sea level rise and inundation, etc. A supply of biodiversity credits associated with verifiable risk reduction would help businesses to satisfy expectations under climate- and nature-related risk disclosures (i.e. TCFD and TNFD). The relevant market motive is ‘enlightened self-interest’ where businesses are investing in risk reductions to mitigate material risks across their value chain.

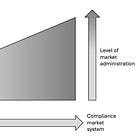

In the long-term (late-2020s and beyond), there is a need to transition to biodiversity credit markets that extend beyond nature-based carbon and risk reduction, and to support contributions toward societal goals such as climate mitigation and reversing biodiversity loss. Developing a market for contribution claims will take significant market education, and it is unlikely that many businesses will never be persuaded to invest in ‘biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake’. Consequently, in the longer term, the Government will need to consider public finance and/or compliance mechanisms to broaden funding for nature repair and regeneration. This could be achieved by a compliance biodiversity market (e.g. mandated purchase obligations, or quotas that businesses need to achieve by acquiring tradable certificates), or by using new or existing tax revenue to fund public procurement of credits.

Next:

Back to: