Introducing Toha’s dual-token system

The Toha Network is using digital token technology to enable people to pay for, and be paid for, nature-based work.

Toha is creating an impact payment system for climate action and nature regeneration. This is the missing market infrastructure to enable funders to invest in verifiable impact, and frontline communities to get paid for work in service to nature.

But what are the mechanics behind this system? This post dives into the tokenomics behind the Toha system.

What are digital tokens?

Tokens are digital bearer assets which can be transacted online – from platform to platform.

One of the better known use-cases of digital tokens is cryptocurrencies, like bitcoin, ether, and solana. However, it would be a mistake to treat digital tokens as equivalent to cryptocurrencies. Tokens are tools that can be used for multiple purposes. Currency is one use-case, but there are many others including data sharing, authentication of identity, intellectual property (IP), transaction fee payments, collectibles, securities, and governance.

Even cryptocurrencies can be put to a variety of purposes. The jury is still out on whether bitcoin can succeed as a store of value, but other cryptocurrencies are already playing more humdrum roles as mediums of exchange. For example, Visa is using Circle's USDC stablecoin to improve the speed of cross-border payments, as an alternative to slow and costly international wire transfers. As a stablecoin, the value of USDC is pegged to the value of USD, so it is not vulnerable to the speculative volatility of untethered cryptocurrencies like bitcoin. In this way, digital tokens can serve a function as a secure mode of transaction.

How is Toha using tokens?

Toha is piloting a dual-token system. Dual-token systems are not uncommon in the emerging world of Web3, because this enables systems with better incentive structures, features, and functionalities. In turn, this creates more value for token holders and end users.

The two tokens in Toha’s system are MAHI and TOHA.

The MAHI token represents a unit of work in service to nature and climate (see our MAHI explainer for further detail). By purchasing the credit, the buyers of MAHI are releasing secure funds for frontline action, as well as funding the development of Toha’s platform infrastructure and impact data technology. As an algorithmic stablecoin in the future, its price will be tethered to the rate of the living wage in Aotearoa New Zealand, which is currently NZD$26.

TOHA is a network token which generates rights to data and governance in the Toha system. Holders use TOHA to pay the transaction fees to access, use and share data in the system. TOHA also grants governance rights to influence the future direction of the market cooperative. This enables the future transition of the Toha system into a decentralised autonomous organisation (or DAO).

Thus, these different tokens – MAHI and TOHA – serve different functions in the Toha system. MAHI enables the transfer of funds to repairing and regenerating our landscapes, while TOHA grants rights to the benefits of the Toha system.

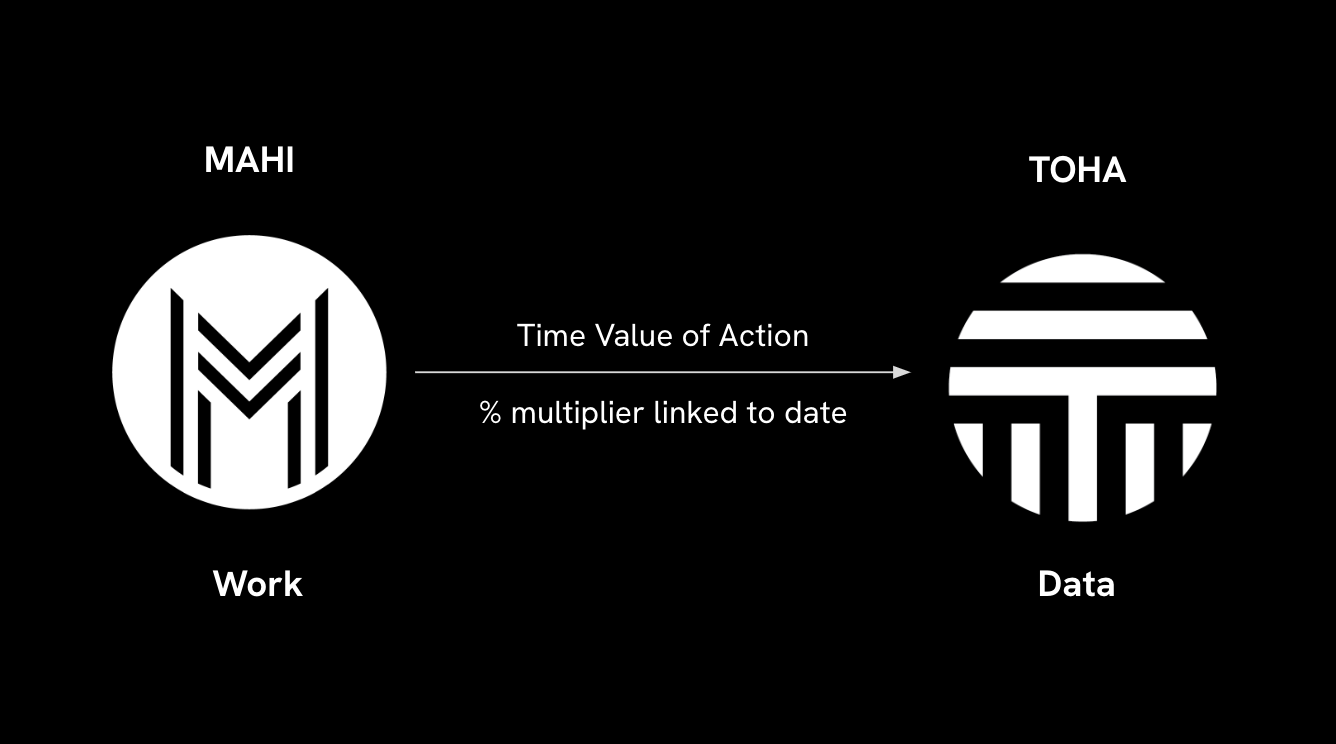

As noted earlier, this dual-token system also creates opportunities to adjust incentives through how these tokens interact. A key interaction is the capacity to exchange MAHI units for TOHA network tokens. In the initial phase of the Toha system, in order to acquire TOHA, one must convert MAHI that they already hold. This is akin to a currency swap where MAHI, which represents proof of work, is exchanged for TOHA, which represents rights to data and governance.

Through the design of this swap, the Toha system has in-built incentives for early action which reflect the urgency of the challenge on climate change and biodiversity loss. The swap occurs using a fixed exchange rate which accords greater value to early action than the same action in the future. We call this the Time Value of Action (or TVA). Essentially, a multiplier is applied to MAHI, but this multiplier is discounted over time in the lead-up to 2030. (This is the subject of a later post.) So, the earlier MAHI is earned, the greater the value of TOHA it can be swapped for.

The dual-token structure enables the Toha system to reward the risks taken by early movers, and to increase their exposure to value uplift in the system. For example, acquisitions of MAHI and TOHA, as well as associated data, can be disclosed by companies to demonstrate to shareholders and customers that they are actively managing climate and nature-related risks in their value chain. This incentivises companies to prioritise intergenerational stewardship over short-termism.

Token economics gives us unprecedented opportunities to trial new economic models, to scale up its impact, and rewire the economy for regenerative outcomes.

Digital tokens: the building blocks of Web3

Digital tokens are one of the defining technologies of Web3, the next emerging phase of the internet.

Web 1 was the internet of email and web pages, where users were passive receivers of information. Web2 is the internet that emerged at the start of the millennium, a proliferation of tools for creating, sharing, discussing and remixing digital content. It also became the era of very large online platforms, like Facebook and Google, which generate extraordinary profits by appropriating the data that people produce on their platforms. The defining feature of the platform economy is that power accrues to the point of aggregation – i.e. the platform.

Web3 is the internet of decentralised ownership and, therefore, distributed power. It is, presently, an emerging rather than a prevailing paradigm, but it is already manifest in many applications – in finance, philanthropy, gaming, governance and more.

Digital tokens are central to Web3 because tokens enable ownership. Critically, tokens enable the ownership of data that could otherwise be appropriated by others, such as large centralised platforms, without their full consent or fair share of the benefits. Consequently, tokens could unlock the longstanding vision of a ‘dignified information economy’ where ‘data creators directly trade on the value of their data... Direct buying and selling of information-based value between primary parties could replace the selling of surveillance and persuasion to third parties.’

The critical features of digital tokens are:

programmable to serve a multitude of purposes that require scarcity and verifiable ownership.

composable to connect seamlessly across multiple platforms with integrated functionality.

self-custodial insofar as we can hold tokens in a digital wallet, or transfer them securely to a third party.

permissionless and censorship resistant by being cryptographically protected from interference by third parties.

transferable peer-to-peer so that the exchange of tokens can occur directly between buyers and sellers.

The Toha system is applying this functionality to work in service to nature. In this sense, Toha belongs to a wider global movement of regenerative finance (ReFi) which applies Web3 technologies to accelerating sustainability.

MAHI tokenises the data produced by the verification of nature-positive work, so that frontline communities can capture the value it generates for the wider economy.

TOHA tokenises network rights, so that holders can capture the value uplift in Toha’s digital infrastructure as transactions increase. TOHA network tokens give rights to access, share and use verifiable data, as well as governance rights going forward.

These functions are enabled by the unique technological affordances of Web3. Of course, not every token use-case will be meaningful, nor even positive. The initial phase of cryptocurrency – as even its champions admit – was too often characterised by greed and recklessness. But this is hardly unique among new technologies. And it would be remarkable if there were not ways to harness Web3’s novel capabilities to address complex contemporary challenges.

Tokens are a tool and, like any tool, they can be used for good or bad. The real question is what purpose tokens are being put to, and what values govern their use.

In Toha’s case, token economy design is governed by principles of generosity to future generations, trust through relationships, community decision-making, data sovereignty, and transparency. Guided by these principles, we are building a token economy to serve nature and its caretakers.

Further reading

Alex Tapscott (2023). Web3: Charting the Internet's Next Economic and Cultural Frontier. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Callaghan Innovation (2023). Digital Assets and Decentralised Finance: The opportunities and the challenges for New Zealand. Auckland: Callaghan Innovation.

Web3NZ: an open source initiative built to surface and publish insights that address challenges faced by New Zealand founders, creators and businesses innovating in Web3.

I've had a good look at the Toha website and I'm deeply impressed with the innovation involved. I'm very interested to understand if Toha can be aligned to post-growth thinking.

A shift to a post growth economy involves nature regeneration, which requires funding and therefore mechanisms for moving funds between parties and an exchange of value. Buying the data that demonstrates contribution to regeneration in a specific network, supply chain or region seems a fair exchange for councils, governments and businesses that have set targets. However, VC funding, impact investing, speculative investing and biodiversity credits are all mechanisms of the growth economy. So I have a few questions from a post growth perspective, so I can understand Toha in ways that I have not been able to garner from the website.

1. Toha Foundry is VC-backed. What is the VC exit plan?

2. It seems likely that TOHA holders, who have governance rights, would vote to allow TOHA tokens for biodiversity offsets. Why not block that possibility?

3. How is the matter of longevity/durability of regenerative outcomes taken into account in the lifespan of TOHA tokens?

4. What is meant by the phrase " true value of environmental action"? It seems like projects most desired by investors will attract more money? How are communities taken into account, to channel funds to their preferred projects?

5. Is large scale speculative investment seen as the most likely way to fund larger or a greater number of projects?

6. How is future use of project areas accounted for in the impact outcomes? For instance, is the ecological prioritised over the socio-ecological? Are the experts being engaged on building the templates a mix of physical and social scientists?

7. Are cultural outcomes involved? Should cultural outcomes be valued in a marketplace?

While regeneration outcomes are likely, I don't yet see how Toha's model challenges the growth-oriented economic paradigm. It seems more like Toha is trying to show that a growth economy approach can be regenerative. I'd love to understand the post-growth attributes, if these can be separated out. Thanks.

Can you explain to me a bit further how a MAHI converts to a TOHA?